The Times: How statins might have spared my mother from dementia

A study published this week suggests that statins might be the latest to join the arsenal against Alzheimer’s. It’s a tablet millions of people pop daily, my husband among them. My mother, who died of dementia, also took statins — but only after having had a stroke in her seventies. Is it possible that had she taken them earlier in her life, she would have been spared from the development of this cruel disease?

Irish Times

The author enlists her investigative journalism skills to understand her mother’s illness and, later, to learn how she might save herself from the same neurodegenerative fate.

Detecting Dementia

Dementia may feel like a wrecking ball, but it’s not simply absent one day and fully present the next. No, it settles in, makes itself at home and lingers in the shadows for 10, 15, or even 20 years.

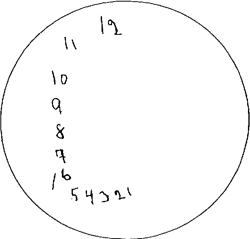

Testing for dementia by asking patients to draw a clock, walk and talk, stand on one leg

I watched my mother draw a clock while she was in a brain rehabilitation centre after her stroke. Until then, I did not know how common a test it was, how often it was used – or why.

The clock drawing test – or CDT – is used regularly to assess several mental processes. Over the past two decades, it has become a key tool in early screening for cognitive impairment – especially dementia.

You might expect it to be simple: drawing a clock that shows the time, say, at six o’clock: a circle, numbers, a big hand, a little hand.

Imagine having dementia. ‘Virtual’ tour simulates clumsy hands, painful feet, filmy vision

It was not hard to imagine how I might have fared in my mother’s shoes. I would have battled to pick up a mug of tea and navigate it to my mouth without spilling. Experiencing the same effect as headphones playing senseless sounds in my ears, I would not have been able to focus or think straight.

And then I remembered that into my mother’s confusing, frustrating world and through the non-stop hiss and rasp of unwelcome sounds and disembodied voices, there was I – her carer – insisting it was time for a shower or that she must finish her juice or go to the loo.

Did my words get through to her? Or did they just add to the upsetting noises in her head?

The reality of caring for a parent who is gripped by the nightmare that is dementia

Breakfast was once eaten enthusiastically. Mum declared everything delicious, especially the marmalade she ate every day, but professed never to have eaten in her life. Near the end breakfast was a miserable exercise in spoon-feeding. Using the telly as distraction I might force another mouthful in.

Can you prevent dementia? Here’s what to try

Dementia, I discovered, isn’t just common — the UK’s biggest killer for a second year running — and it’s about more than lost memories. It stole Mum’s bearings so she couldn’t orientate herself (“Where am I?”), her family (“Who are you?”), her mobility (“What do I do with my feet?” when I urged her to walk) and, in the end, it stole her.

The Irish Times: Dementia: At lunchtime, my Mum knew I was her daughter. By evening, nothing

Sometimes dementia is a loaded gun; you’re going to get the single bullet in a chamber anyway, whatever you do: Russian Roulette. Sometimes it isn’t. The only thing that I know for certain now is that it is not inevitable with age.

Irish Independent: ‘The day my mother forgot who I was’ – how Alzheimer’s changed my mum and me

People asked me afterwards, a little incredulously: “Was it really so sudden?” Yes. One day, late in 2019, between lunch and tea, my mother forgot me. I sat across a table from her at one meal and she was entirely confident who I was. That evening: “Tell me”, she asked, “When did we first meet?”

New Scientist: A fresh understanding of OCD is opening routes to new treatments

OCD is complex and commonly misunderstood, with a limited number of treatment options. But in recent years, the mechanisms in the brain and body that drive it are finally being pinned down, revealing an elaborate picture involving genetics, various brain networks, the immune system and even the bacteria in our gut. In turn, this growing understanding is opening up new possibilities of tackling this life-sabotaging condition.

The Times: Me and my mother: the most moving dementia story you’ll read

The evening my mother forgot who I was — who I am — was just like the one that had come before, and the one before that. Weeks of evenings all alike. I puzzled about that later. Why that evening? Why so sudden? So that at lunchtime she knew I was her daughter and by nightfall she didn’t. Six hours later. That’s all it took.

How to prevent dementia: does this Amazonian tribe hold the key? It has an 80% lower incidence than in the West

The Tsimané are an indigenous people from the Bolivian Amazon in South America. You have probably never heard of them. I had not. I had to look up how to pronounce Tsimané: chee-mah-nay.

And yet this small group is extraordinary. A few years ago, scientists studied them to understand their exceptional heart health: 85 per cent had almost no evidence of the calcification of the arteries that is the marker for atherosclerosis. Even those who did have some had very little.

I asked my mother’s neurologist what caused her stroke. ‘Depression,’ he said

Depression, says Professor Craig Ritchie, the chief executive and founder of Scottish Brain Sciences, “may well be an upstream trigger for physical health”. It might even have been a significant risk factor for the Alzheimer’s disease that my mother suffered from in the last six years of her life.

People may present with depression later in life as a consequence of dementia but increasingly, research points to depression in early and midlife as a risk factor for developing dementia.

How dental health may impact brain health; experts describe how poor oral hygiene is linked to higher risk of developing dementia

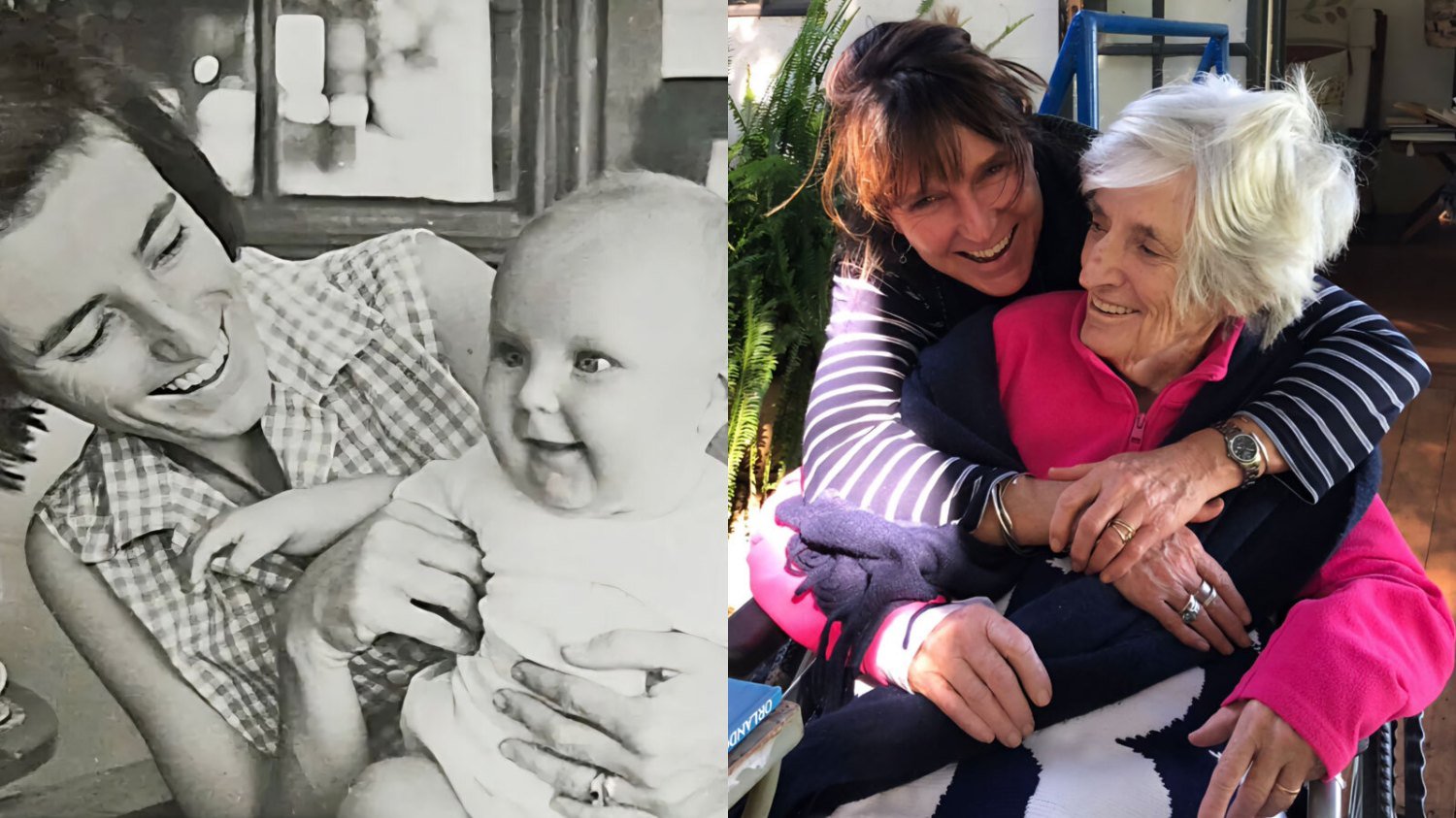

In a photograph of my mother on my desk, she is smiling broadly, an even, white-toothed smile. It was taken 18 months before she died. Her dementia was evident everywhere in our lives by then – but not in that picture: from the photo you’d never guess. She looks self-possessed and whole. In fact, she looks like a commercial for geriatric dental care with that wide, white smile.

What can music do for dementia patients? A lot – experts explain

A kind reader wrote to express gratitude for the Post’s series of articles on dementia. He was 85 years young and still active, although only going to the gym “four times a week now”, which made me smile. In his spare time, he listens to music CDs.

How protecting your heart health may prevent dementia

What is good for your heart is good for your brain.

This is the message many doctors share. They include Dr Albert Hofman, chair of the department of epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard University, in the US state of Massachusetts.

We may finally know how cognitive reserve protects against Alzheimer's

We have known for almost three decades that some peoples’ brains can function normally even when riddled with the plaques and other damage associated with dementia, due to an enigmatic capacity called cognitive reserve. Yet despite growing evidence of its importance, it has been challenging to pin down how this quality operates in the brain.

‘I felt guilt and fear that I had caused my daughter’s OCD’

The diagnosis felt like a gut-punch. Had I done something as a mother to cause this? Had I failed to do something to stop it happening? I felt both guilt and fear – guilt because, as parents, we shape our children. If my daughter struggled with mental illness, had I damaged her in her early years?

My mother has dementia – these are the lifestyle changes I've made to avoid the same fate

People often say, “It’s not your mother, it’s her dementia.” An unhelpful observation.

I know: I know that when my mother is unkind or impossibly difficult it’s because her empathy and characteristic sweetness are being eaten away by Alzheimer’s. Understanding that the fundamental changes in her are because of disease do not make them easier to live with.